If you've used AI coding assistants or chatbots with tool use, you know the feeling. You ask it to do something moderately complex, and then you wait. And wait. The agent thinks, calls a tool, waits for the result, thinks again, calls another tool, waits again. Each step is sequential. Each step adds latency.

I've been building with agents at work, and this sequential bottleneck has been driving me crazy. A task that conceptually should take seconds ends up taking minutes because the agent can only do one thing at a time. It's like having a brilliant assistant who can only use one hand.

So when I started hearing about "agent swarms" - systems that spawn multiple sub-agents working in parallel - I got curious. But I also got skeptical. Is this just marketing hype? Is "more agents" really different from "more prompts"? What does it actually mean for a swarm to be trained rather than just prompt-engineered?

I went down the rabbit hole. I read the Kimi K2.5 technical report, dug into the research on multi-agent reinforcement learning, and tried to understand what's actually going on under the hood. And here's what I found: the shift from sequential to parallel agents isn't just an optimization - it fundamentally changes the failure modes, the training challenges, and even what "intelligence" means in this context.

This post is my attempt to explain agent swarms the way I wish someone had explained them to me. By the end, you should be able to answer these questions:

- What does it mean for an agent swarm to be trained, not prompt-hacked?

- Why does parallelism change the failure modes compared to single-agent tool use?

- What's the real bottleneck: model intelligence or critical-path latency?

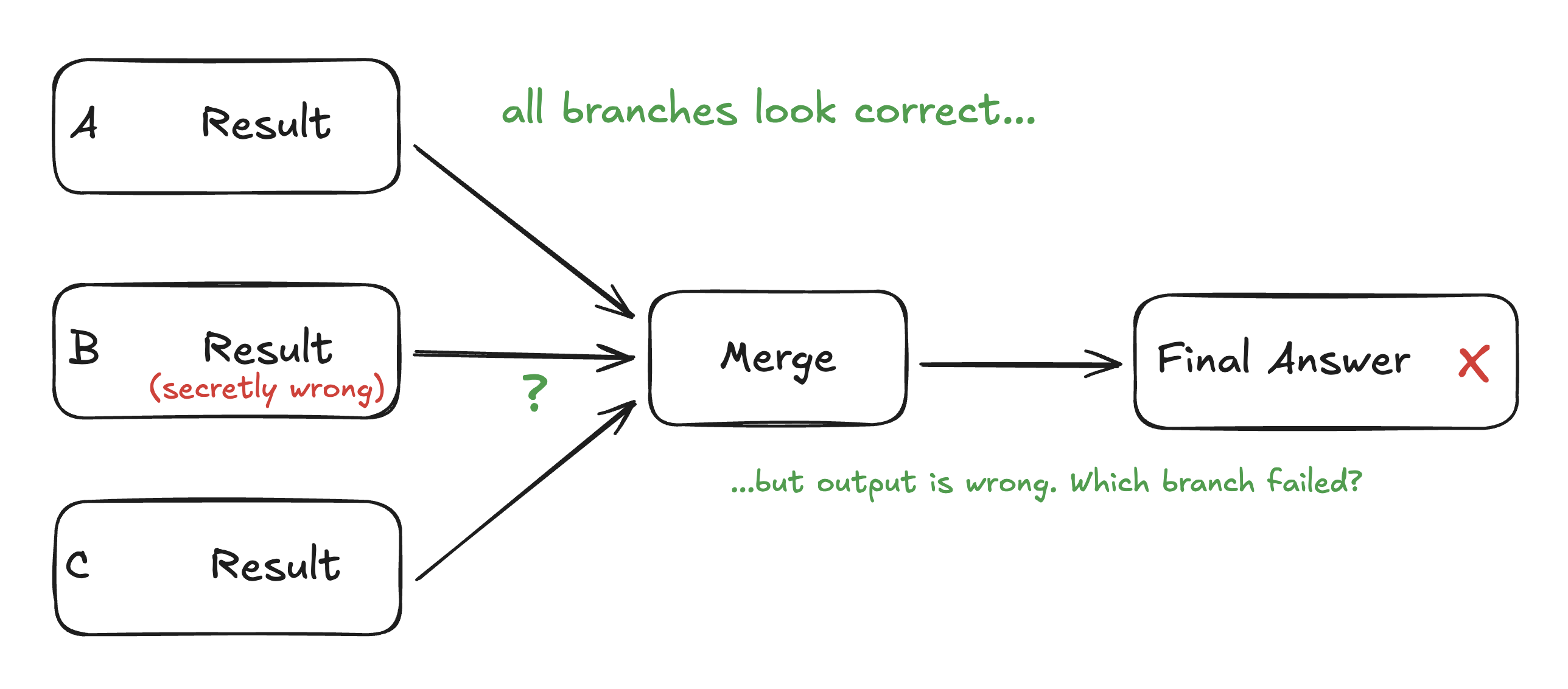

- How do you assign credit/blame when parallel branches produce a wrong answer?

- When do swarms actually help vs. when are they overkill?

Let's dig in.

The Sequential Agent Problem

Let's start with how most AI agents work today. Whether you're using ChatGPT with plugins, Claude with computer use, or some custom agent framework, the basic loop looks the same:

- Think: The model reasons about what to do next

- Act: It calls a tool (search, code execution, API call, etc.)

- Observe: It receives the tool's output

- Repeat: Back to thinking, incorporating the new information

This is the ReAct pattern, and it works. But there's a problem hiding in plain sight.

The Wall-Clock Pain

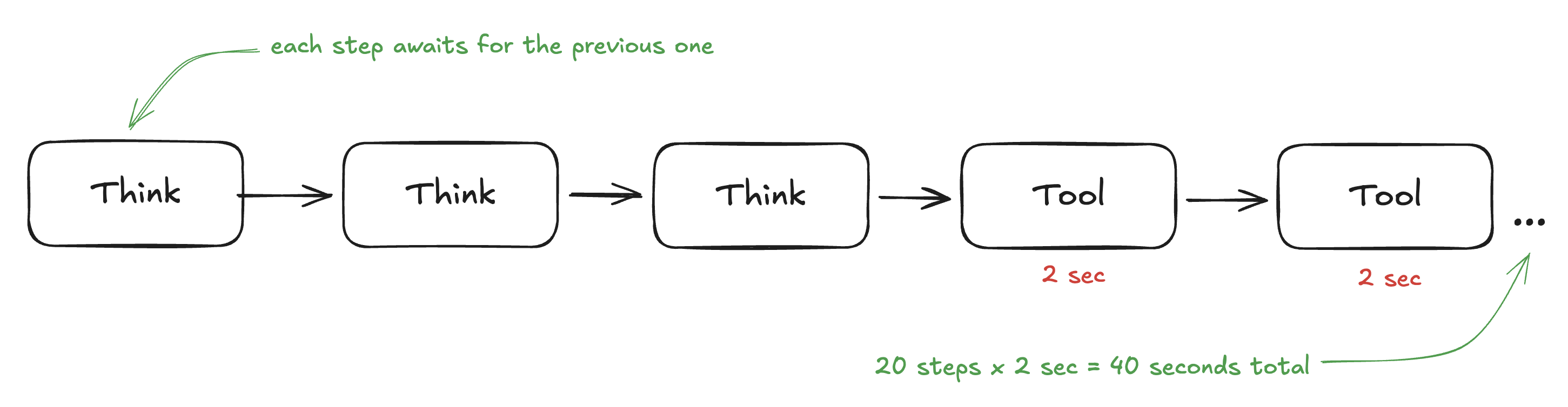

Every iteration through this loop takes time. The model needs to generate tokens (let's say 1-2 seconds). The tool call needs to execute (maybe 2-5 seconds for an API call or file operation). Then the model processes the result and generates more tokens.

For a simple task - "what's the weather in New York?" - this is fine. One tool call, done.

But for complex tasks, the number of steps explodes. Consider a coding task: "Find the bug in this codebase, write a fix, and verify it works." That might involve:

- Reading 5-10 files to understand the codebase

- Searching for relevant functions

- Running the existing tests to see the failure

- Writing a fix

- Running tests again

- Maybe iterating if the fix didn't work

That's easily 20+ tool calls. If each cycle takes 5 seconds, you're looking at nearly 2 minutes of wall-clock time - even though the actual "thinking" work might only be a few seconds total.

The insight: The bottleneck isn't the total amount of work. It's the sequential dependency chain. You can't run test number 2 until test number 1 finishes. You can't write the fix until you've read the files. Every step depends on the previous one.

Or does it?

Critical Path vs Total Work

Here's a mental model that changed how I think about agent efficiency. I call it the "physics of agents," and it boils down to two concepts:

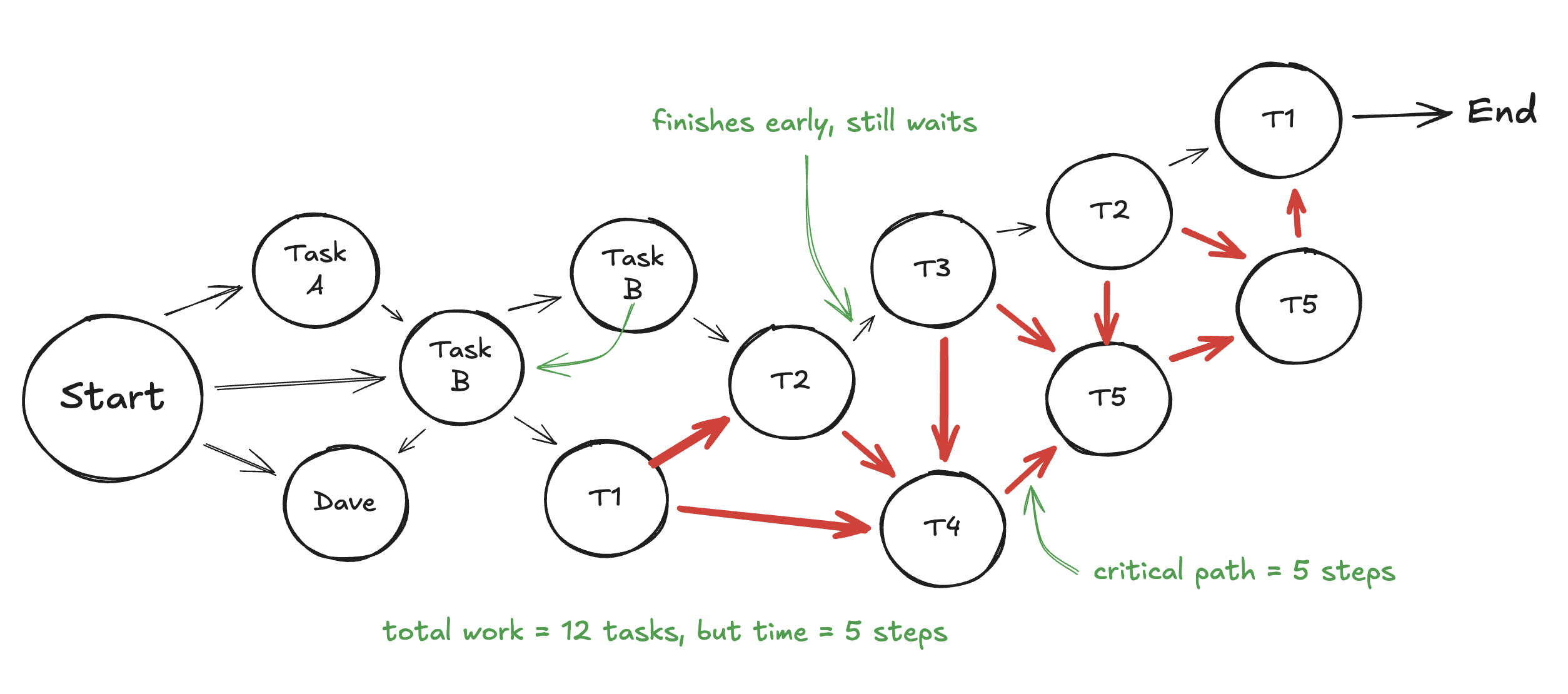

Total work: The sum of all operations that need to happen. If you need 20 tool calls, your total work is 20 tool calls.

Critical path: The longest chain of operations where each step depends on the previous one. This is what actually determines how long the task takes.

Let me give you a concrete example. Say you're researching a topic and need to:

- Search 3 different databases

- Read 4 academic papers

- Synthesize everything into a summary

In a sequential agent, you'd do these one at a time: search 1, search 2, search 3, read paper 1, read paper 2, etc. Total time = sum of all operations.

But here's the thing: the three searches don't depend on each other. Neither do reading the four papers (once you have them). The only true dependency is that synthesis needs all the inputs.

If you could parallelize:

- Run all 3 searches simultaneously → time = max(search times), not sum

- Read all 4 papers simultaneously → time = max(read times), not sum

- Then synthesize

The critical path drops from ~8 sequential steps to ~3 parallel stages. Same total work, fraction of the time.

Amdahl's Law for Agents

If you've studied parallel computing, you might recognize this as Amdahl's Law in disguise. The law says that the speedup from parallelization is limited by the sequential portion of your task.

If 50% of your work is inherently sequential (step B must follow step A), then even with infinite parallelism, you can only get a 2x speedup. The sequential portion becomes the bottleneck.

For agents, this has a clear implication: the real bottleneck isn't model intelligence or total compute - it's critical-path latency. A smarter model that still runs sequentially will still be slow. A dumber model that can parallelize effectively might finish faster.

This is why "agent swarms" matter. It's not about having more agents for the sake of it. It's about shortening the critical path.

What "Agent Swarm" Actually Means

Okay, so parallelism is good. But what does an "agent swarm" actually look like? Is it just running multiple prompts at once?

Not quite. And this distinction matters.

Fake parallelism: You could take any agent and just run 5 copies of it on different parts of a problem. But this doesn't actually help if:

- The copies don't know about each other and duplicate work

- The task has dependencies that aren't respected

- There's no way to meaningfully merge the results

Real parallelism requires something smarter: a system that understands the task structure, figures out what can be parallelized, spawns the right sub-agents, and coordinates their outputs.

The Orchestrator Architecture

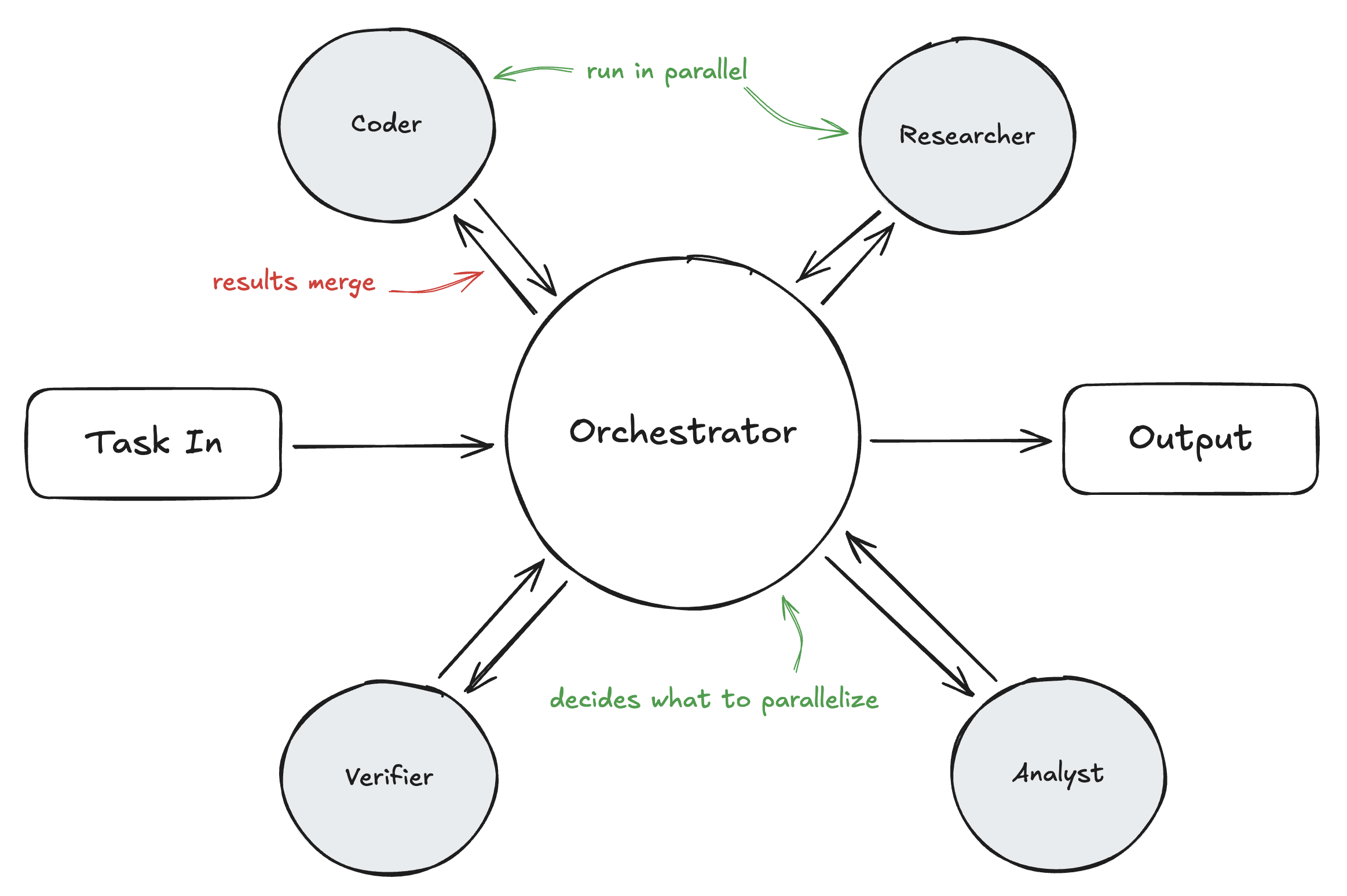

The architecture that's emerged for this looks like a hub-and-spoke model:

- Orchestrator: A central agent that receives the task, decomposes it into subtasks, and decides which can run in parallel

- Sub-agents: Specialized (or general-purpose) agents that each handle a subtask

- Merge step: The orchestrator collects results and synthesizes the final output

Kimi K2.5, which I've been studying as a case study, takes this to an extreme. According to their technical report, their Agent Swarm can:

- Spawn up to 100 sub-agents dynamically

- Coordinate up to 1,500 tool calls across them

- Achieve 4.5x wall-clock speedup compared to single-agent execution

The key word there is "dynamically." The orchestrator doesn't follow a fixed workflow. It looks at the task and decides, on the fly, how to decompose it. Maybe this task needs 3 sub-agents. Maybe that one needs 50. The decomposition itself is learned.

Trained, Not Prompt-Hacked

Here's where it gets interesting. You could build the orchestrator architecture I just described with clever prompting:

"You are a task orchestrator. Given a complex task, break it into subtasks. For each subtask that doesn't depend on others, spawn a sub-agent. Wait for results. Synthesize."

This is what I'd call "prompt-hacking" - using instructions to get emergent behavior from a model that wasn't specifically trained for it. It can work! But it's brittle. The model might:

- Over-decompose (spawn 50 agents for a task that needs 2)

- Under-decompose (do everything sequentially despite parallelization opportunity)

- Miss dependencies (run step B before step A completes)

- Struggle with the merge step (can't synthesize 20 partial results coherently)

The alternative is to train the orchestration behavior directly. Make parallelism a learned skill, not an emergent hack.

PARL Explained

Kimi K2.5 uses something they call PARL - Parallel-Agent Reinforcement Learning. The core idea is elegant, and it addresses a fundamental training challenge.

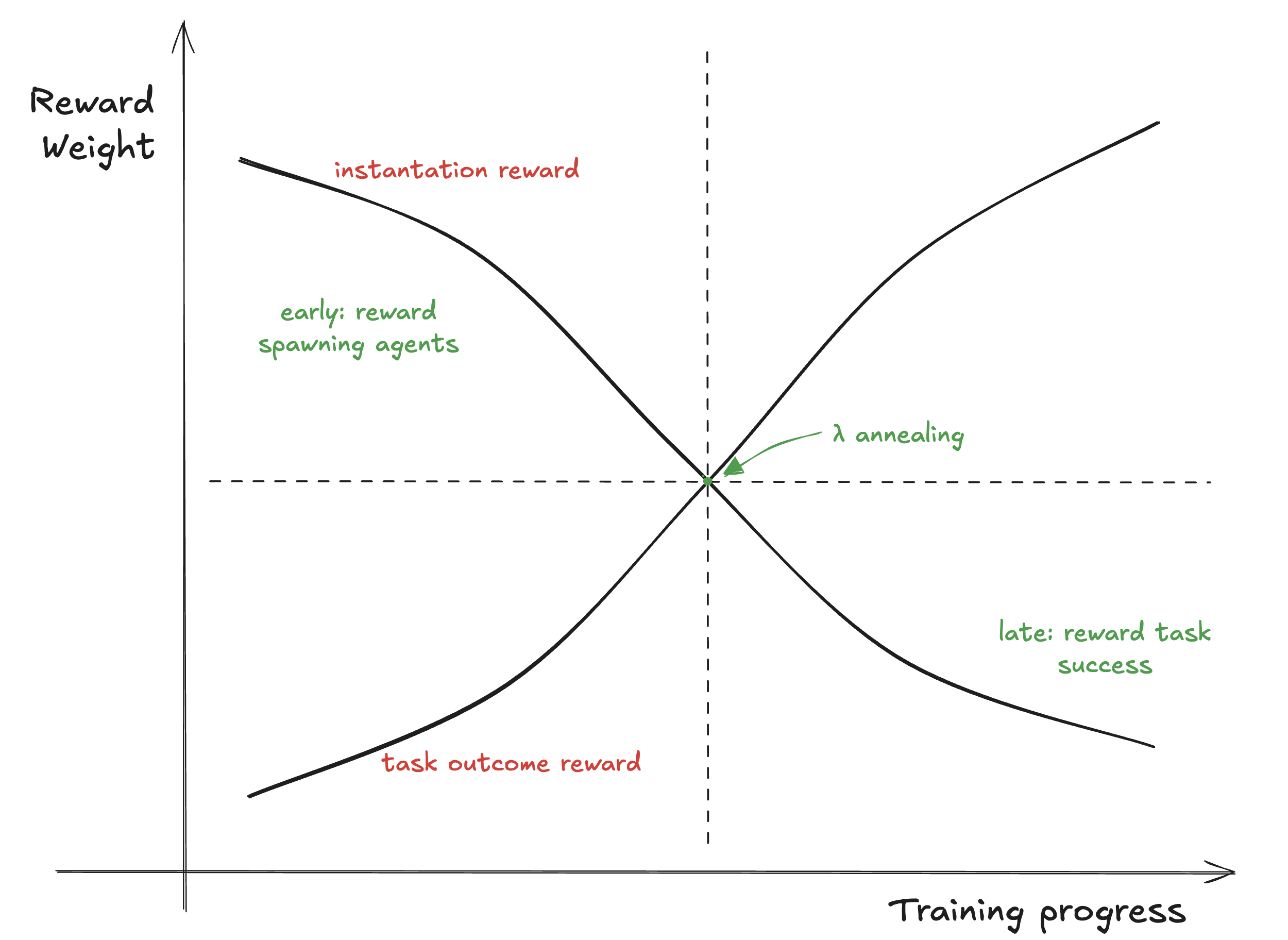

The problem: If you just train on task success (did the agent get the right answer?), the model has no incentive to parallelize. Sequential execution works fine for getting correct answers - it's just slow. From the model's perspective during training, why bother with the complexity of spawning sub-agents?

The solution: Staged reward shaping that explicitly rewards parallelism early in training.

PARL uses two reward components:

- Instantiation reward: Rewards the model for spawning sub-agents and running them concurrently. This is high early in training.

- Task outcome reward: Rewards the model for actually completing the task correctly. This becomes dominant later in training.

The balance between these is controlled by a parameter λ that anneals from 0.1 to 0.0 over the course of training. Early on, the model gets significant reward just for attempting parallelism. Later, it only gets reward for parallelism that actually helps task completion.

There's also a clever trick: they introduce a "computational bottleneck that makes sequential execution impractical." Essentially, they make the training environment hostile to sequential approaches, forcing the model to discover parallel strategies.

The result is a model that doesn't just can parallelize - it knows when to parallelize. That's the difference between a skill and a hack.

The Critical Steps Metric

If you want to measure whether parallelism is actually helping, you need the right metric. "Total tool calls" is misleading - you could make 1,000 parallel calls, but if they're all redundant, you've wasted compute without reducing latency.

K2.5 introduces what they call "Critical Steps" - a latency-oriented metric inspired by critical path analysis:

Critical Steps = Σ(orchestration overhead + max sub-agent time per stage)

In other words: for each "stage" of parallel execution, you count only the slowest sub-agent (since you have to wait for all of them anyway). Then you sum across stages, plus any orchestration overhead.

Let me make this concrete with numbers:

Sequential execution:

- 20 tool calls × 2 seconds each = 40 seconds

Parallel execution (4 branches of 5 tool calls each):

- Stage 1: max(5 calls × 2 sec) = 10 seconds (all branches run in parallel)

- Plus orchestration overhead: ~2 seconds

- Total: 12 seconds

Same 20 tool calls, 3.3x faster. But this only works if the branches are truly independent! If branch 2 secretly depends on branch 1's output, you're back to sequential.

The Critical Steps metric captures this: it only rewards parallelism that actually shortens the critical path. Spawning more sub-agents doesn't help your score unless they're doing genuinely parallel work.

The Credit Assignment Problem

Now we get to what I think is the hardest part of training agent swarms - and something that's not talked about enough.

In a sequential agent, if something goes wrong, debugging is relatively straightforward. You can look at the trace:

- Step 1: Read file → worked

- Step 2: Parse data → worked

- Step 3: Make API call → failed

- Step 4: Never reached

Step 3 is the problem. You know exactly where to look.

Blame in Parallel Systems

In a parallel system, this gets much harder. Imagine:

- Sub-agent A: Researches topic X → returns result A

- Sub-agent B: Researches topic Y → returns result B

- Sub-agent C: Researches topic Z → returns result C

- Orchestrator: Merges A, B, C → produces wrong final answer

Where did it go wrong? Maybe result B was subtly incorrect. Maybe results A and C were fine but contradicted each other. Maybe the merge logic itself was flawed. Maybe B was actually fine but got drowned out by A and C.

This is the credit assignment problem, and it's combinatorial. With n branches, there are 2^n possible combinations of "which branches contributed to the failure." For 10 branches, that's over 1,000 possibilities. For 100 branches (K2.5's max), it's... a lot.

This matters for training because reinforcement learning depends on assigning credit. If the final answer is wrong, you need to adjust the behavior that caused it. But if you can't figure out which behavior caused it, you can't learn effectively.

The research literature on multi-agent RL has developed various approaches to this:

- Value decomposition: Try to decompose the global reward into per-agent contributions (VDN, QMIX)

- Per-branch intermediate rewards: Give feedback to each sub-agent individually, not just at the end

- Trajectory-level analysis: Look at the full execution trace to identify problematic patterns

I suspect PARL does some combination of these, though the exact details aren't public. What I can say is that this is fundamentally harder than single-agent RL, and it's one of the reasons "just spawn more agents" doesn't automatically work.

Failure Modes of Swarms

Let's be honest about when swarms go wrong. This isn't just theoretical - these failure modes show up in practice, and understanding them helps you know when not to use swarms.

1. Serial Collapse

This is the most common failure mode: the orchestrator has the ability to spawn parallel sub-agents but defaults to sequential execution anyway. It's like having 10 employees available but still doing everything yourself.

Why does this happen? Sequential execution is "safer" from the model's perspective. There are fewer moving parts, less coordination required, lower risk of conflicting outputs. Without explicit training pressure (like PARL's instantiation reward), models naturally drift toward sequential approaches.

2. Fake Parallelism

The model spawns multiple sub-agents, but the work isn't actually independent. Maybe sub-agent B is secretly waiting for sub-agent A's output before it can proceed. The DAG looks parallel, but the execution is still sequential.

This is particularly insidious because it looks like the system is working correctly. You see multiple agents, you see parallel execution, but your wall-clock time doesn't improve.

3. Coordination Overhead (The Telephone Game)

Every time information passes between agents, there's a risk of degradation. The orchestrator summarizes the task for sub-agents. Sub-agents summarize their results for the orchestrator. Each summarization loses nuance.

Research from Anthropic found that in some multi-agent setups, "subagents spent more tokens on coordination than on actual work." When coordination overhead exceeds the parallelism benefit, you've made things worse.

4. Error Propagation

A swarm is only as good as its weakest link. If one sub-agent consistently produces bad output, it can poison the entire merge step. Unlike sequential execution where you can potentially catch and correct errors, parallel execution commits to all branches simultaneously.

5. Agent Overwhelm

This is like "overthinking" but for multi-agent systems. Too many sub-agents produce too many inputs, and the orchestrator or downstream agents can't process them all coherently. The system generates more information than it can synthesize.

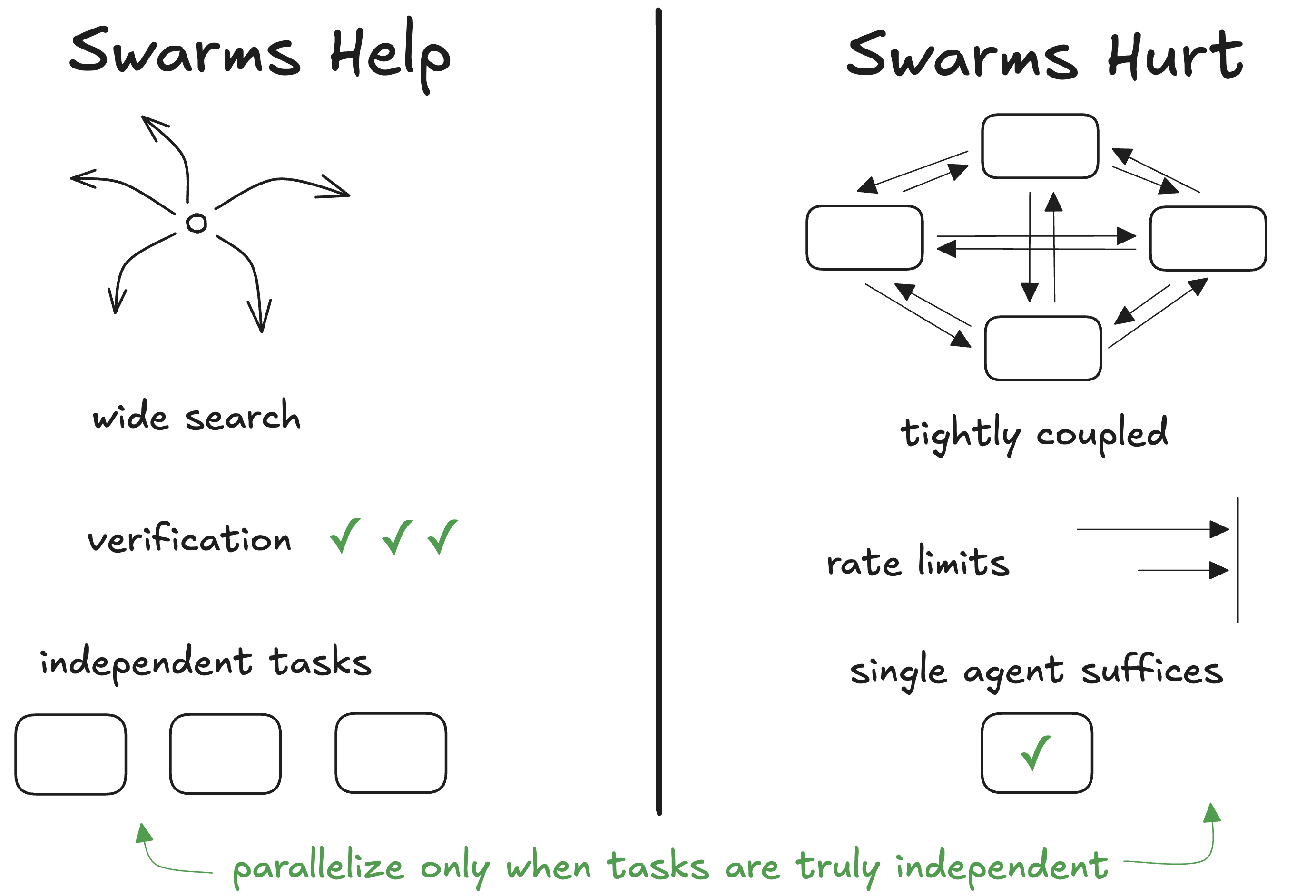

When Swarms Help vs Hurt

Given all these failure modes, when should you actually use swarms?

Swarms help when:

- Wide search problems: Exploring multiple solution paths simultaneously. If you're searching for a bug that could be in any of 10 modules, checking all 10 in parallel beats checking them one by one.

- Verification tasks: Multiple independent checkers catch different types of errors. One agent checks logic, another checks formatting, another checks security.

- Multi-source synthesis: Gathering information from many independent sources. Research across multiple databases, APIs, or documents.

- "Committee" decisions: When you want multiple perspectives and can meaningfully aggregate them. Code review by multiple agents, each focusing on different aspects.

- Context overflow: When a single agent's context window can't hold all the necessary information, but you can distribute it across multiple specialized agents.

Swarms hurt when:

- Tightly-coupled reasoning: When every step depends on every other step. Mathematical proofs, complex logical arguments, chain-of-thought that can't be decomposed.

- Rate-limited APIs: If your parallel tool calls all hit the same rate limit, parallelism doesn't help - it just generates errors faster.

- Single agent suffices: If the task is simple enough that one agent can handle it cleanly, the coordination overhead of a swarm just makes things worse.

- Lack of architectural understanding: If agents don't understand how pieces fit together, parallel failures become parallel disasters. As one researcher put it: "Perfect agent coordination accelerates failure when agents lack architectural understanding."

The honest advice: Start with a single agent. Master prompt engineering and context management. Understand your task's true dependencies. Measure actual parallelization potential. Only when you hit genuine single-agent limitations should you consider swarms.

Anthropic's multi-agent documentation puts it well: "A well-designed single agent with appropriate tools can accomplish far more than many developers expect."

The Connection to Message Passing

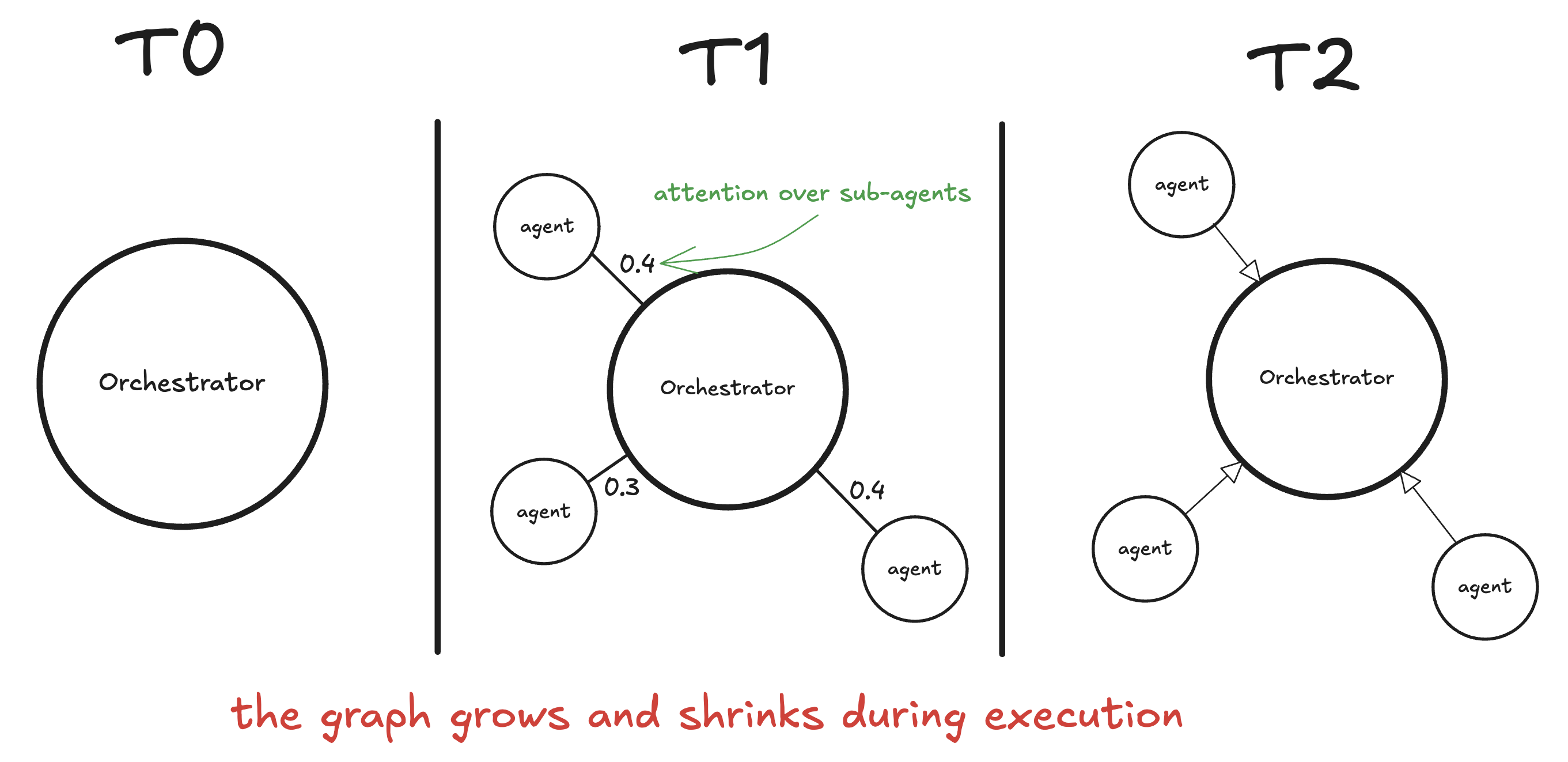

If you read my previous post on Graph Attention Networks, you might notice something familiar here.

In GATs, we had nodes in a graph passing messages to each other. Each node aggregated information from its neighbors, with attention weights determining how much to listen to each neighbor. The key insight was that not all neighbors are equally important - the network learns which connections matter.

Agent swarms have the same structure. The orchestrator is a central node. Sub-agents are neighbors. The orchestrator decides which sub-agents to spawn (which "edges" to create), and when aggregating results, it implicitly weights them (attention over sub-agent outputs).

But there's a twist: the swarm graph is dynamic. In a GAT, the graph structure is fixed - you're learning weights over existing edges. In a swarm, the structure itself changes during execution. At t=0, you have just the orchestrator. At t=1, it spawns 5 sub-agents (5 new edges). At t=2, some sub-agents finish and their edges disappear. At t=3, maybe new sub-agents spawn based on intermediate results.

This is why I think of swarm orchestration as "message passing over a dynamic graph." The orchestrator is learning not just which edges to weight highly, but which edges to create in the first place.

If that sounds hard to train, it is. But it's also why trained orchestration (PARL) beats prompt-hacked orchestration. Learning to construct the right graph is a skill that improves with practice.

Conclusion

Let me leave you with the key insight that ties this all together:

"Scaling out changes the unit of intelligence from a single chain-of-thought to a coordination policy."

In a single agent, intelligence is about generating the right sequence of thoughts and actions. In a swarm, intelligence is about decomposing problems, delegating appropriately, and synthesizing results. It's a different skill.

To recap the five questions we set out to answer:

- What does it mean for a swarm to be trained? It means the orchestration behavior - when to parallelize, how to decompose, how to merge - is learned through reinforcement learning (like PARL), not hand-coded through prompts.

- Why does parallelism change failure modes? New failure modes emerge: serial collapse, fake parallelism, coordination overhead, error propagation, and agent overwhelm. These don't exist in sequential systems.

- What's the real bottleneck? Critical-path latency, not total work. Parallelism helps only when it shortens the critical path.

- How do you assign credit/blame? It's hard. With n parallel branches, there are 2^n possible blame attributions. This is an active research area in multi-agent RL.

- When do swarms help vs hurt? They help for wide search, verification, multi-source synthesis, and committee decisions. They hurt for tightly-coupled reasoning, rate-limited APIs, or when a single agent suffices.

I'm still exploring this space. The next things I want to dig into are heterogeneous swarms (where different sub-agents have different capabilities) and hierarchical orchestration (orchestrators that spawn orchestrators). But that's for another post.

If you're building with agents and hitting the sequential bottleneck, I hope this gave you a framework for thinking about when and how parallelism might help. And if you're skeptical of the hype around "agent swarms" - good. A healthy skepticism will serve you better than blindly adding more agents.

As always, feel free to reach out on Twitter if you have questions or want to chat about this stuff.